United States and the Indian Ocean Region: The Security Vector

The principal US security goals in the Indian Ocean Region are the safekeeping of its trade and energy sea lines of communication (SLOCs), maintaining a force sufficiently strong to balance or counter most events in the Middle East and elsewhere along the ocean’s littoral, and ensuring the naval primacy it has retained in the ocean since the Second World War. It is to meet these objectives that Washington has established military bases at Diego Garcia in the British Indian Ocean Territory and in the Persian Gulf. Other major bases are located at Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa, and in Ethiopia. Each of these bases can cater to between five hundred and five thousand personnel. Strategically placed, they could host rapid reaction forces that could cater to virtually any circumstance quickly. The locations of these bases frees the US from the necessity to pursue more ambitious goals in the region as the potential power inherent in them is sufficient to stabilise it.

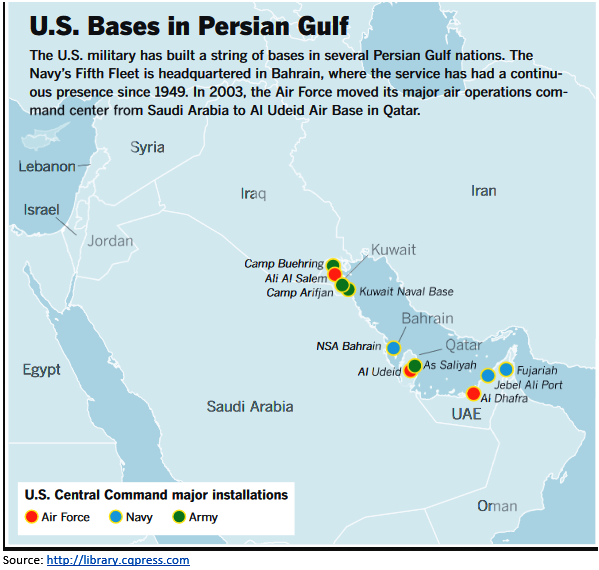

It is in the Persian Gulf, however, that the most US military bases and personnel are situated. According to the 2016 Index of US Military Strength, there are around fifteen thousand US troops stationed in Kuwait, five thousand in the UAE and seven thousand in Bahrain. While the US has withdrawn the bulk of its troops from Saudi Arabia, there is no information on how many are still stationed there. In Oman, US personnel numbers now hover around two hundred because Omani facilities are no longer used for air support operations. There are no permanent military bases in Jordan but the US conducts many training exercises with Jordanian forces. Lastly, while troop numbers in Iraq had dropped to around the 150 personnel who guarded the US embassy in Baghdad, that number has since shot up to around 1,600 with the influx of US military personnel who are employed in training Iraqi forces in their fight against the Islamic State terrorist group. In 2012, according to one report, there were ‘about 125,000 US troops in close proximity to Iran: 90,000 soldiers in/around Afghanistan on Operation Enduring Freedom; some 20,000 soldiers deployed ashore elsewhere in the Near East region; and a variable 15,000-20,000 afloat on naval vessels.’

In addition to these bases, there have been reports of secret bases in Saudi Arabia from where drones are used to strike “terrorist groups” in Yemen. The US bases in the Persian Gulf are home, collectively, to large numbers of fighter and other aircraft and naval ships, including facilities to cater to modern aircraft carriers. As the map below demonstrates, Iran, which is still perceived as an aggressive regional power, nuclear agreement or not, is surrounded by these bases.

Given the nature of the bases and their usefulness in securing the region, it is doubtful if they will be closed anytime soon, even if the US military budget continues to decrease. It must be understood, however, that Iran was not the primary target when these bases were established. That function was to secure the energy resources in allied countries, to protect Israel and to eliminate threats to US interests in the region. The general level of distrust of Iran by the US, however, suffices by itself to keep the bases operational for the foreseeable future. It was even alleged late last year that the Pentagon, with the sanction of the Obama Administration, planned to create a network of these bases in the Middle East to battle the Islamic State terrorist network.

Another military base is situated in the tiny African state of Djibouti. Camp Lemonnier is the largest US military base in Africa (officially, at least, it is the only such facility on the continent), and hosts around four thousand personnel. Djibouti overlooks the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which leads to the Suez Canal, one of the world’s busiest shipping routes. The volume of traffic attracts pirate attacks, mostly from Somali pirates, hence a major function of this base lies in countering those attacks in conjunction with French and Japanese personnel who are also based in Djibouti. More recently, China has begun constructing its own base there. The US base in Djibouti is ideally situated to keep an eye on the war in Yemen, which lies a little over thirty kilometres across the strait, and also on a restless Somalia to the south.

The secretive, albeit controversial, military base at Diego Garcia in the British Indian Ocean Territory, which forms part of the Chagos Archipelago (see map below), enables the US to keep a close watch on the major trade and energy SLOCs from and to China, as well as maritime traffic between the base and the east coast of Africa. It has allegedly been used to control some operations in Yemen and Afghanistan and also as a stopover for the CIA’s rendition programme. This base, named Camp Justice (the name is ironic given the manner in which the base was acquired), was also used to keep watch over South Asia during the Cold War.

There could also be, in addition to the established military bases noted above, plans for future bases. One of the more important of these could be situated on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. This group of islands, situated approximately 2,900 kilometres north-west of Perth, already has an airstrip that is used by the Royal Australian Air Force. There have been reports that the islands could be used by the US to launch drones. In November 2011, Defence Minister Stephen Smith declared, after President Obama had visited Australia to announce with Prime Minister Julia Gillard that up to 2,500 US Marines would rotated in Darwin, that the islands could be used as a joint Australia-US air force base. If a military base is constructed on these islands, it could complement the one on Diego Garcia, the lease of which runs out later this year.

MALACCA DILEMMA

While the base on Diego Garcia could track, say, Chinese shipping that passes between it and Sri Lanka on its way to the Strait of Malacca en route to the South China/West Philippine Sea, a similar base situated on the Cocos Islands could keep watch over shipping that bypasses the Strait of Malacca to use the deeper-channel Sunda Strait or the Lombok Strait. China is acutely aware of the dangers it faces, in the event of conflict with either India or the US, of its energy supplies being disrupted at the Strait of Malacca; Beijing terms this scenario its “Malacca Dilemma”. By developing a base on the Cocos Islands, the US would be just as well placed to terminate Chinese energy and trade SLOCs that seek to pass through the Sunda or Lombok Straits. It is conceivable that this scenario has been partly responsible for China’s efforts to seek alternatives, such as overland pipelines through Pakistan, to pump the energy products it procures from the Middle East, notably Iran, and East Africa (Sudan) into its western provinces.

It is, however, the maritime competition in the Indian Ocean between China and India that will, arguably, interest the US the most in the shorter term. Given its economic downturn, the US seeks like-minded democracies in the Indo-Pacific region to balance China. It has strong relationships with Australia, Japan and South Korea, all three of which, interestingly, have or will have US bases on their territories. It lacks a similar partner in the eastern Indian Ocean and, therefore, would like to have India join an informal coalition to balance China. India could, given its own economic rise, a growing sense of its importance in the region and beyond and, importantly, a rapidly developing navy, fill that role admirably.

India has made it clear that it does not wish to be drawn into any alliance or coalition that aims to contain China but is aware, nevertheless, of China’s increasing activity in the Indian Ocean, a region that India sees as its zone of influence. When a Chinese submarine docked in Sri Lanka in September 2014, for instance, it signalled a possibility that could herald closer ties between Sri Lanka and China. Since around seventy per cent of Sri Lanka’s transhipment traffic comes from India, New Delhi felt it could lose economically and also face a loss of influence in its backyard. The same submarine again docked in Colombo in November 2014, underscoring India’s concerns. The Sri Lankan presidential election held soon afterwards saw Maithripala Sirisena take office. He halted several Chinese-backed projects and placed them under review. He also announced in January 2016 that Sri Lanka would scrap a plan to buy fighter aircraft in a deal worth US$400 million.

China, however, had its hooks deeply embedded into Sri Lanka, which uses around one-third of its revenues to service a US$8 billion Chinese debt. To offset this, Sirisena has agreed to let China recommence its port construction project, albeit to a reduced extent. This turn of events has caused concern once again in New Delhi. It is aware that China is slowly but surely increasing its footprint in the Indian Ocean. This concern can only be compounded by the news that a Chinese submarine docked in Pakistan for the first time in May 2015 and that China plans to sell Pakistan advanced submarines. Couple these developments with the fact that China reportedly informed India that it would begin patrols in the Indian Ocean using its nuclear-powered submarines, the reasons for India’s concern US become evident.

It is, arguably, this which has forced New Delhi to develop its ties with Washington. Unsurprisingly, it seeks technology transfers from the US, including military technology related to drones, manned aircraft and aircraft carriers. Washington, for its part, has persuaded India to enter into a logistics agreement. It is likely that their converging interests will see India and the US become close partners, even if not outright allies, in the Indian Ocean.

This, obviously, suits Washington’s strategy of passing some of the responsibility for maintaining security in the Indian Ocean Region to regional partners. For India, the partnership will enable it to access technology that it would find difficult to procure elsewhere and enable it to further develop its own security strategies, including establishing a manufacturing sector that could produce weapons systems and platforms that utilise these technologies, thus reducing its dependence upon other countries. In effect, then, the Indian Ocean has become, from this perspective at least, an extension of the South China Sea.

The US has been forced by economic circumstances to divest itself of many of the security responsibilities it carried since the end of the Second World War. That notwithstanding, it remains the most powerful economy in the world and, arguably, still possesses the strongest military. It has adapted to its changed circumstances by creating partnerships of varying degrees with regional stakeholders to ensure that its interests in the Indian Ocean, in this case, are not negatively affected. It is probable that its primacy in the Indian Ocean will continue for many years to come.( Note: Views/opinions expressed in this paper are of the author)

-By Lindsay Hughes, Research Analyst,

Indian Ocean Research, Future Directions International

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments