Myanmar: A Violent Push to Shake Up Ceasefire Negotiations

The Brotherhood Alliance comprises the Arakan Army (AA), Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA).

The Arakan Army (AA) was formed in 2009 under the patronage of the Kachin Independence Organisation at its headquarters on the China border in Laiza. The group emerged as a serious force from 2015, when it began participating in attacks in Shan State together with the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and Kachin Independence Organisation. Around this time, its fighters also began to infiltrate into southern Chin State, close to the border with Rakhine State. In January 2019, it launched major attacks in Rakhine State and has been engaged in heavy fighting with the military there for the past nine months.

The Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) traces its roots to the Palaung State Liberation Army formed in 1963. After the latter signed a ceasefire with the military government in 1991, remnant forces in Kayin State continued to fight against the military together with the Karen National Union as the Palaung State Liberation Front. The Front was largely inactive, however, until 2009, when it established the TNLA as its new armed wing, under the patronage of the Kachin Independence Organisation. The TNLA has fought regularly against not only the Myanmar military but also militias allied to the military, such as the Pansay militia, and the Shan State Army-South, the armed wing of the Restoration Council of Shan State.

The Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) was formed after forces led by Pheung Kya-Shin (Peng Jiasheng) broke away from the collapsing Communist Party of Burma in 1989. It was the first ethnic armed group to sign a ceasefire with Myanmar’s military regime, which had taken power the previous year. The ceasefire held for two decades until 2009, when the Myanmar military invaded the Kokang region after the MNDAA refused to become a Border Guard Force under military control. The military ousted Pheung Kya-Shin and put a rival faction in charge of the Kokang region.

The attacks launched on 15 August in northern Shan State were unusual in their boldness but should not have come as a surprise, given rising tensions over ceasefire negotiations and recent Myanmar military pressure.

The Brotherhood Alliance’s objectives were to underline its ability to strike at key economic infrastructure, to shift pressure off AA forces in Rakhine State and to reset bilateral ceasefire talks.

Not only did the three groups perceive a need to relieve pressure on the AA in Rakhine, but tensions between them and the government had been rising for some time due to negotiations over proposed ceasefire terms. Despite the military’s unilateral ceasefire, an increasing number of clashes had been reported in June and July.

The Myanmar military’s response has so far been subdued. But there is no guarantee that its restraint will continue; a major counteroffensive is still possible.

The willingness of both sides to engage in dialogue is promising, but given recent disagreements, a fundamental rethink of negotiations will be required to improve prospects for bilateral ceasefires.

As long as the three groups remain outside the peace process, prospects for an end to Myanmar’s conflicts remain dim. Their status has been the pivotal issue in the process for the past five years, causing fragmentation among Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups that has undermined efforts at dialogue.

Bilateral ceasefires that bring the three insurgent groups into the peace process would be an important step forward, if only because it would mean an immediate end to fighting in large parts of Rakhine and Shan States. The insistence that the groups give up territorial gains is unrealistic, however, particularly for the AA, and Naypyidaw should abandon it.

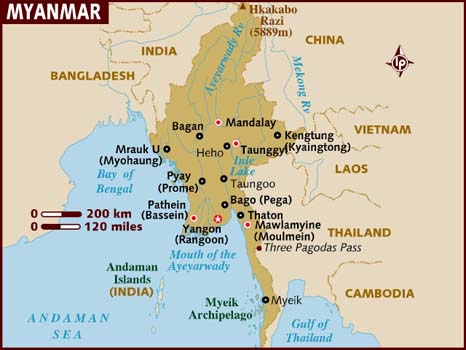

In the early hours of 15 August, hundreds of Brotherhood Alliance fighters – predominantly TNLA soldiers – staged coordinated attacks on targets in Pyin Oo Lwin township, Mandalay Region and Naunghkio township, in northern Shan State.

Targets included a battalion headquarters in Naunghkio; Pyin Oo Lwin’s Defence Services Technological Academy, which was hit by three 107mm rockets; a narcotics control checkpoint; the Goktwin bridge and a neighbouring police outpost on the Mandalay-Muse highway; and a military battalion. On 17 August, insurgents destroyed three more bridges on the route from Hseni to the border at Chinshwehaw, in Shan State’s Kokang region.

The attacks, which were successful partly because the targets were lightly guarded, have exacted a high economic toll.

Though subsequent attempts to destroy bridges or attack battalions were less effective, and the assailants incurred significant casualties, the infrastructure damage and instability created have halted trade at two important border crossings, Muse and Chinshwehaw. Goods worth billions of dollars – mainly Myanmar’s agricultural products – pass through these points each year.

A significant attack was not unexpected. The groups had warned Myanmar’s military as far back as April 2019 to halt offensives in Rakhine State against the AA or face joint military action. On 12 August, they repeated the threat and announced the creation of the Brotherhood Alliance, which they seem to have formed for the purpose of carrying out the attack three days later.

Not only did the three groups perceive a need to relieve pressure on the AA in Rakhine, but tensions between them and the government had been rising for some time due to negotiations over proposed ceasefire terms. Despite the military’s unilateral ceasefire, an increasing number of clashes had been reported in June and July.

If the 15 August attacks represent a rejection of this current ceasefire proposal, they are also a push for the status enjoyed by most of Myanmar’s other armed groups – many of which have far less military capacity and public support. Such recognition seems inevitable both for the parties to reach bilateral ceasefires and for the peace process to be able to move forward with credibility and legitimacy.

In the meantime, both sides should adhere to their respective unilateral ceasefires and refrain from further attacks, particularly those that might put civilians at risk. They must also allow aid to reach those in need and ensure that aid workers are not targeted or put at unnecessary risk.

To give renewed impetus to bilateral ceasefire negotiations, the military should broaden its unilateral ceasefire to Rakhine State and lengthen the time horizon. Given its significant influence over both parties, China is well placed to encourage an end to the fighting and renewed dialogue.

– Excepts from latest Crisis Group report on Myanmar

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments