In China, a President's Attempt to Disarm Challengers

China tried its best to keep up the appearance of harmony in March, when the National People’s Congress held its annual plenary session. But outside Beijing, the carefully scripted show did not go as planned. In economically depressed Heilongjiang province in the country’s northeast, thousands of coal miners working for a state-owned enterprise protested for three days over unpaid wages. Eventually, the People’s Armed Police (PAP), China’s paramilitary police force, was dispatched to break up the demonstrations.

Simultaneously, moves were being made at the National People’s Congress to reform the convoluted command structure of the PAP. The force’s current structure subordinates it to both China’s civilian government and the Central Military Commission; it both backs up China’s civilian police to maintain order and defends the Communist Party as an auxiliary armed force. But the force’s political commissar, Gen. Sun Sijing, proposed to amend the Armed Police Law to give more authority over the PAP to President Xi Jinping and the Central Military Commission, which Xi chairs. Should it pass, the amended law could lay the groundwork to change one of the most important organizational aspects of the PAP: its dual leadership structure.

Simultaneously, moves were being made at the National People’s Congress to reform the convoluted command structure of the PAP. The force’s current structure subordinates it to both China’s civilian government and the Central Military Commission; it both backs up China’s civilian police to maintain order and defends the Communist Party as an auxiliary armed force. But the force’s political commissar, Gen. Sun Sijing, proposed to amend the Armed Police Law to give more authority over the PAP to President Xi Jinping and the Central Military Commission, which Xi chairs. Should it pass, the amended law could lay the groundwork to change one of the most important organizational aspects of the PAP: its dual leadership structure.

The People’s Liberation Army is in the middle of its most sweeping reforms to date, so it is no surprise that the paramilitary police force would undergo changes of its own. Yet the PAP’s reforms are less about making the force function better and more about Xi preparing to crack down on political adversaries ahead of the 19th Party Congress in 2017. The proposed reforms would concentrate China’s remaining armed forces in the hands of Xi, disarming anyone from the Party bureaucracy or local governments who could challenge his rule. If the reforms occur, the question will be whether the PAP, under more singular management, will still be as responsive to domestic unrest.

Duties and Command Structure

The PAP, established in 1982, numbers over 600,000 and is tasked with internal security. Armed with military-grade equipment and trained to handle mass unrest, the PAP shores up China’s public security system when the civilian police forces are insufficient. In peacetime, the PAP helps control ethnic and labor unrest by dispersing protests, dispensing disaster relief and performing counterterrorism operations. In wartime, it becomes second-line reserve force of the People’s Liberation Army, guarding the army’s rear, protecting communications and supply lines, and ensuring interior stability.

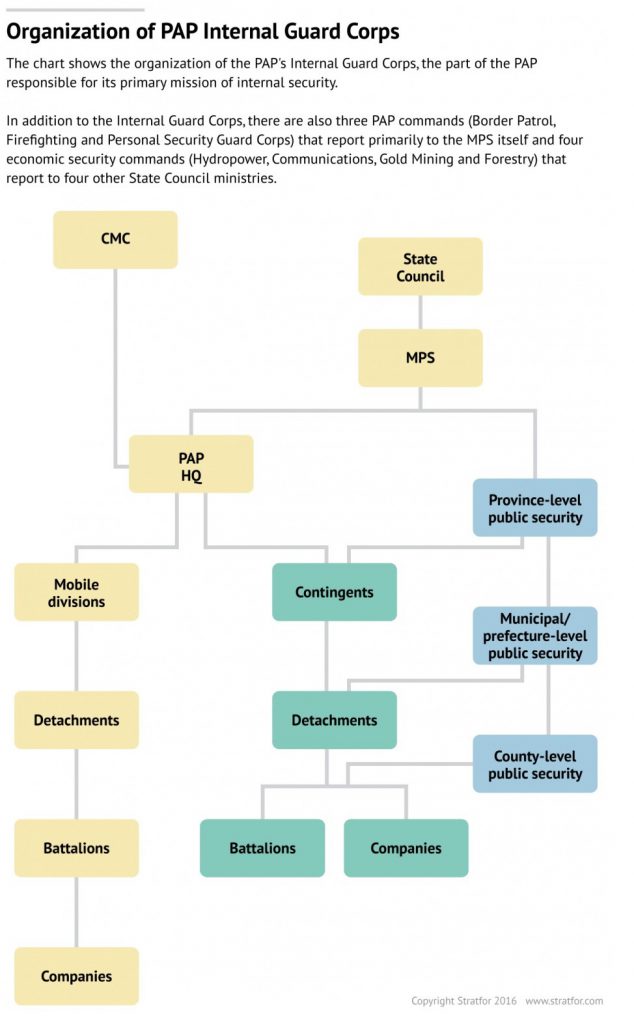

Reflecting the PAP’s role in both civilian and military affairs, the force reports to both the State Council — primarily the Ministry of Public Security, China’s police ministry — and the Central Military Commission. The State Council, China’s Cabinet, is led by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and controls the various ministries of China’s government. Meanwhile, the Central Military Commission, controlled by its chairman, Xi, is the highest authority in the People’s Liberation Army.

Reflecting the PAP’s role in both civilian and military affairs, the force reports to both the State Council — primarily the Ministry of Public Security, China’s police ministry — and the Central Military Commission. The State Council, China’s Cabinet, is led by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and controls the various ministries of China’s government. Meanwhile, the Central Military Commission, controlled by its chairman, Xi, is the highest authority in the People’s Liberation Army.

The divided command and control structure makes the PAP highly fragmented. Officially, the Ministry of Public Security has the legal authority to command the armed police force and funds much of it, though other ministries direct some of the force’s specialized units. The ministry also provides guidance by appointing the public security head at every level of government as the first political commissar of its local PAP force. Local Party committees then direct most of the force’s day-to-day public security operations, which gives the public security chief immense power over the force. It makes the PAP, unlike the People’s Liberation Army, the only armed force answerable to China’s government apparatus. Nonetheless, the Central Military Commission also directs the PAP by appointing leaders, training forces and providing operational oversight.

The outcome is a paramilitary force that is capable of quickly responding to major protests at the behest of local governments but is also prone to abuse. For example, in 2005 a PAP unit fired into a crowd of protesters under the orders of local Party authorities in the town of Shanwei, killing around 20 people and making security matters worse. To combat this and other examples of excessive force and unilateral action, Beijing passed the Armed Police Law in 2009, restricting the use of the armed police force by local governments. Still, prefecture and provincial governments retained their ability to employ the force, as was the case when the soon-to-be-purged Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai dispatched an armed police convoy to chase down his former head of public security, whose defection to the U.S. Consulate in Chongqing triggered Bo’s political downfall. Despite its passage, the Armed Police Law left the dual leadership structure intact, preserving the PAP’s bureaucratic complexity.

Dual leadership has been the defining feature of the PAP since its founding. The force arose when leader Deng Xiaoping decided to relieve the People’s Liberation Army of its duty of handling the increasing number of disturbances brought about by the reform process. But this was not necessarily true for the PAP’s predecessors — People’s Liberation Army soldiers in the service of the Ministry of Public Security after the end of the Chinese Civil War. These internal security forces went through eight organizational iterations since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, including periods when they fell either solely under the Ministry of Public Security’s jurisdiction or that of the Central Military Commission. Even under dual leadership, the relative balance of power has constantly shifted.

This tenuous bond has often reflected political trends. In the 1950s, Mao Zedong expressed consternation that his more orthodox colleagues wanted to strengthen the role of the Ministry of Public Security in commanding the paramilitary police. When Mao sought to bring the government bureaucracy to its knees during the Cultural Revolution, he feared that the State Council and local governments would use the armed police to resist him. The PAP was soon disbanded and its forces placed under military control, making it more difficult for the bureaucracy to have access to an armed force. Unfortunately for Mao, disbanding the PAP made containing the chaos following the Cultural Revolution’s popular mobilization equally difficult.

While the PAP’s confusing command structure has created organizational tension and room for abuse, there does not appear to have been a serious call to eliminate it until now. Gen. Sun Sijing’s proposal is not the same as announcing that the PAP should sever its institutional ties with the State Council, but it implied that the Central Military Commission should adjust and strengthen its hold over the force. Last year, a leaked copy of a military reform plan envisioned the creation of a “national guard” formed out of the PAP, reporting solely to the Central Military Commission. While this is almost certainly subject to intense debate and is by no means final, the discussions demonstrate that there are strong voices in Beijing pushing for the armed police force to diminish or even cut its ties to the Ministry of Public Security.

Why Now?

Although the proposal did not pass by the end of the National People’s Congress plenary session on March 16, it did not need to. Important decision-makers all sit on the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, essentially a bimonthly legislature controlled by the Politburo Standing Committee. While the process will take time, there is clear intent to alter the PAP’s dual leadership model, regardless of whether there is a legal framework to support it.

In fact, reform has been a priority since at least June 2015, when discussions on the amendment proposal began. A military reform guideline published by the Central Military Commission on Jan. 1, 2016, declared that China would “adjust the command and management of the Armed Police,” almost certainly implying changes in the dual leadership structure. Sun’s subsequent emphasis on the system of accountability to the Central Military Commission chairman corroborates this intent. Moreover, the PAP’s responsibility to the State Council was not even mentioned in Sun’s proposal.

At this point, it is not clear whether this is a proposal being pushed from below by the PAP’s top leaders or whether it stemmed from directives from above. But overall changes in the armed police force must be seen in the context of power consolidation. It is notable that Sun and Gen. Wang Ning, the force’s commander, were transferred out of the People’s Liberation Army to their current positions in December 2014 — and apparently initiated the amendment process within the first six months of their appointments. It is also worth noting that in the last contested leadership transition, when Jiang Zemin assumed the presidency in the early 1990s, he sought to bring the PAP to his side, eliminating his opponents’ supporters in the force and replacing them with his own loyalists.

Xi appears to be making the preparations for a similar power struggle — one expected to take place at a particularly sensitive time. Xi is making moves to crack down on the formation of factions ahead of the 19th Party Congress in 2017. China’s consensus-based politics are breaking down, as are Deng-era norms — that cadres defeated in leadership struggles will not be harmed. The lead-up to the 19th congress, where there will be massive turnover in the senior ranks of the Communist Party, is expected to be accompanied by unusually desperate political struggle.

While the PAP is nowhere near as strong as the People’s Liberation Army, it is still a substantial armed force and is one that currently answers to both Xi and Premier Li Keqiang. And while Li may not be a direct political adversary to Xi, lower-level PAP forces are answerable to China’s various regional governments, from which challenges to Xi’s rule may emanate. Xi will centralize as much armed force under his own command as possible, if only to deny its use to anyone else.

Yet adjustments to the PAP command and control will not be without risks. The reason that the PAP was put under dual leadership in the first place was to improve the ability of local governments to manage unrest as it occurred. Around 6 million layoffs are expected over the next two to three years as China proceeds with cuts to overcapacity in bloated heavy industries such as coal and steel. Consequently, the likelihood of large protests similar to those in Heilongjiang will increase. The greatest challenge for Xi will be disarming regional governments while still preserving their ability to quickly react to developing cases of domestic unrest.

-STRATFOR

https://www.stratfor.com/analysis/china-presidents-attempt-disarm-challengers?id=be1ddd5371&uuid=ee38940b-0056-48d4-9b30-9f37d0383810

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments