“China’s Carbon Market – Tale of a Promise & a Perhaps”

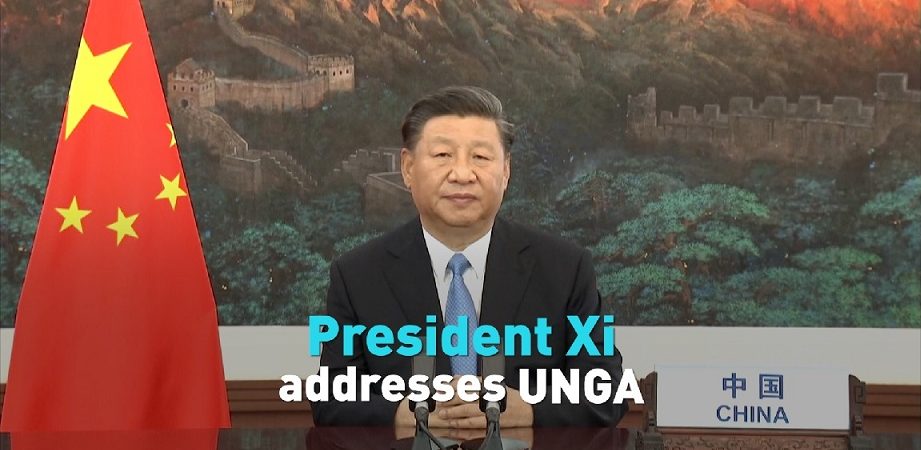

China, the world’s top carbon dioxide producer, has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and to start reducing emissions within the following ten years. At a meeting of the UN General Assembly, President Xi Jinping made the bold promise to a virtual audience of world leaders. Many scholars, including those in China, were taken aback by the pledge, since they had not expected such a bold aim.

China, the world’s top carbon dioxide producer, has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and to start reducing emissions within the following ten years. At a meeting of the UN General Assembly, President Xi Jinping made the bold promise to a virtual audience of world leaders. Many scholars, including those in China, were taken aback by the pledge, since they had not expected such a bold aim.

Despite embracing the power sector in its initial phase this year, China has already surpassed the European Union’s (emission trading system) ETS as the world’s largest ETS, covering 12 percent of worldwide CO2 emissions. The Chinese government has high hopes for the global trading system. They expect it will assist the country in accelerating its energy transition at a “reduced cost” in order to meet its “dual carbon” climate targets of peaking emissions by 2030 and achieving “carbon neutrality” by 2060. However, the ETS’s “benchmark”-based design, limited coverage, and lack of a definite ceiling on emissions raise doubts about whether it will help China meet its climate goals in its current form.

According to the Rhodium Group, China is the world’s largest producer of greenhouse gases, accounting for more than a quarter of global emissions in 2019[1]. More than two-thirds of the country’s emissions come from the power sector and manufacturing, with energy (40%) and industry (29%) accounting for more than two-thirds of the total.

In 2010, China said that it will install an ETS to help regulate these emissions. In 2015, it underlined its clear resolve to do so. An ETS, to put it simply, is a technique of placing a price on carbon. CO2-emitting entities, such as factories or power plants, are issued tradable permits or allowances that allow them to emit a certain amount of carbon. At the end of each cycle, participants must submit permits equal to their actual emissions.

The inauguration of China’s ETS has been frequently postponed. The original date of “during the 12th five-year plan period” (2011-2015) was pushed back to 2016, then 2017. By 2019, a “three-phase development plan” for 2017-2019 predicted a “quick operation phase with maturity” and an ETS that “played a central role in greenhouse gas emissions control.” It was then delayed to 2021.

This “dual carbon” climate pledges provide the strongest possible political signal that the country’s CO2 emissions must peak and then be rapidly reduced to zero. China’s leader has mentioned the national ETS several times in the context of attaining his goals. However, there are still doubts over whether the ETS will genuinely help reduce emissions. Two research studies, both released in April 2021, came up with opposing conclusions on this crucial subject. The national ETS “may be a significant market-based device to help the government fulfil its recently extended climate goals,” according to a joint assessment by the IEA and Tsinghua Institute of Energy, Environment, and Economy (Tsinghua 3E).

Importantly, this conclusion is based on the idea that the ETS will be subject to gradually tougher benchmarks over time, something Chinese officials have yet to promise.

It is also important to note that China’s ETS is essentially a tradable performance standard (TPS): it targets reductions in the CO2 intensity of economic activity (a rate-based system), rather than total CO2 emissions (a mass-based system).

The TPS has the disadvantage of costing more to achieve a given reduction in CO2 emissions. The reason for this is that, unlike cap and trade, the TPS does not fully utilise production reduction as a technique of reducing emissions. This is because, under the TPS, reducing output comes with a cost: the number of emission allowances available reduces in proportion to output size. As a result, covered facilities will have to rely on reduced emission intensities to meet compliance requirements. The cost-effectiveness of the TPS is reduced as a result, according to economic analyses.

Another drawback of the TPS is that the allowable prices generated by the system are unknown. Other emissions trading systems are also affected by this uncertainty.

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment in China, which is in charge of administering the TPS, is seriously contemplating setting a price floor for allowances. The government would set the floor by reducing the supply of allowances as needed to keep the market price from going below it.

So, while many people think China’s new TPS enterprise is off to a strong start, there is still a lot of ambiguity regarding its long-term environmental and economic consequences.

Put simply, President Xi Jinping’s new policy pledge has a lot of potential, but there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how it will develop. Well, the commitment by itself marks a huge stride forward, but matching performance is a spec in the sky. As of now, reducing the Xi promise to a mere talking point! (POREG)

[1]Rhodium Group, China’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Exceeded the Developed World for the First Time in 2019, https://rhg.com/research/chinas-emissions-surpass-developed-countries/

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments