Europe’s Industry faces new crisis, courtesy China

by Poreg’s China watcher*

by Poreg’s China watcher*

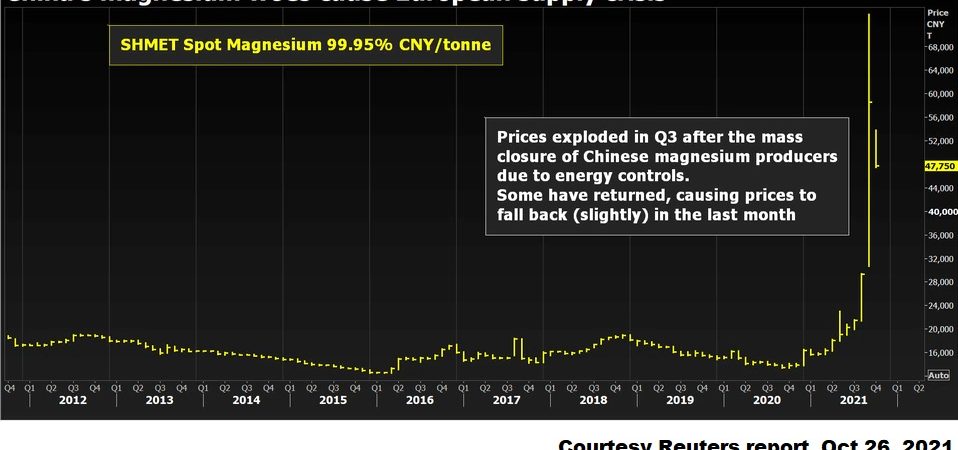

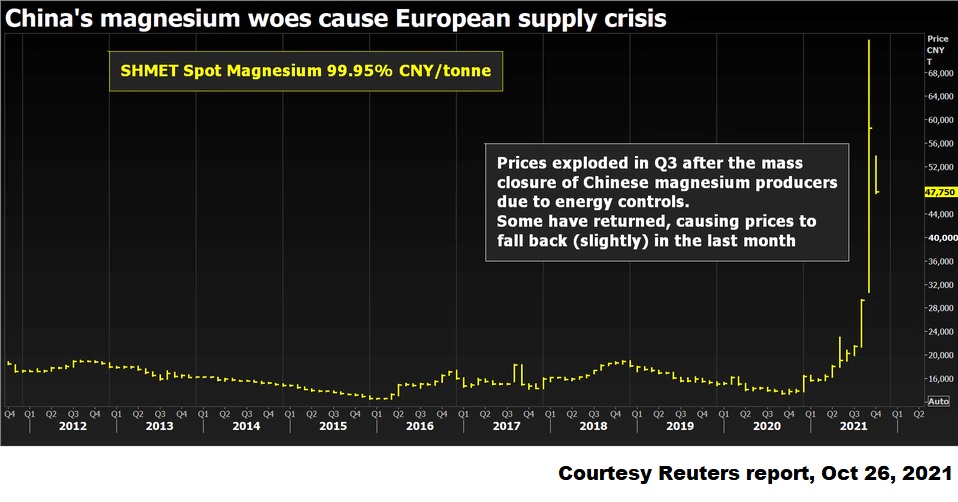

China, which manufactures more than 95 per cent of Europe’s magnesium requirements, has cut back on production leading to considerable disquiet in the European Union (EU), as magnesium is vital to sectors such as cars, aircraft, and electronics. China has cut back production because of the

nation-wide energy shortages. Other producing nations like Russia and Israel find it difficult to fill the shortfall, as China is by far the world’s largest producer.

At the recent EU leaders’ summit ( Oct 21-22, 2021) both Angela Merkel, the outgoing German Chancellor and Andrej Babis, Czech Prime Minister raised the issue, on the heels of the crisis of semi-conductors in Europe.

Both Germany and Italy are Europe’s leading car manufacturers and their concern about the knock-on effect on car production is but natural. While

Chancellor Merkel pointed to the impact on the cost of production of cars, the Czech PM was even more blunt when he said the sector was facing a ‘disaster’.

In the last two decades, China has built a monopoly on the global supply of magnesium. They managed to get their European rivals by engaging in large-scale dumping.

The dependence on China is an embarrassment to the EU at this juncture as it attempts to balance relations with China while trying to break free of its supply chains. Global Times reported (24 October 2021) that while many businesses had resumed production and trading, hurdles and restrictions continued to limit output and could result in a 10 per cent drop in exports of magnesium.

According to a joint statement issued by a dozen EU industry groups,magnesium stocks now risk running out by the end of this month (Nov 2021). With Chinese factories partially closed due to the nationwide energy crisis and exports of magnesium falling rapidly, Europe faces a real challenge. The joint statement warned about “far-reaching ramifications on entire European Union value chains,” and added that the construction and packaging industries are also feeling the heat.

According to a joint statement issued by a dozen EU industry groups,magnesium stocks now risk running out by the end of this month (Nov 2021). With Chinese factories partially closed due to the nationwide energy crisis and exports of magnesium falling rapidly, Europe faces a real challenge. The joint statement warned about “far-reaching ramifications on entire European Union value chains,” and added that the construction and packaging industries are also feeling the heat.

If not resolved immediately thousands of businesses across Europe could be threatened impacting their entire supply chains and jobs that rely on them. The industry bodies have therefore called for urgent action by the EU. There are few guarantees that China will immediately respond or provide long-term assurances.

The shortage also calls into question the EU leaders’ plans to put pressure on China to adopt drastic measures to cut the use of coal in line with the resolve of the international COP26 Climate Change Conference held in Glasgow.

However, the change in last few years within Europe has been its more vocal and strident views on China’s handling of its human rights in Tibet and Xinjiang. For several decades, German industry looked the other way when it came to China’s record of treatment of its ethnic minorities, as managers and engineers from companies like Siemens and Volkswagen helped transform the country into Germany’s largest trading partner.

In recent months, as Chinese President leader Xi Jinping has tightened the country’s surveillance state and taken on an increasingly belligerent tone with the West, Germany’s China strategy, has come under review. This is so both within government and amongst leading industrialists.

For instance, Siegfried Russwurm, the head of the Federation of German Industries (BDI) said, “Human rights are not the internal affairs of states,” and added that companies had “the obligation to define red lines for their global commitment themselves,” instead of waiting on their own governments to do so.

This change in perspective is because German business, which is more exposed to China than any of its European partners, faces a difficult choice between preserving a crucial trade relationship and maintaining the liberal ideals that Germany holds dear.

The BDI recently published a paper titled “Responsible Co-existence with Autocracies.”

The paper underscores the importance for Western firms to “lead by example” on questions of human rights and environmental protection” but also makes it clear that severing commercial ties with authoritarian regimes isn’t a viable option.

This hedging strategy shows that German business has reached the crossroads and is negotiating a new path for itself on China. The logic used is that companies must generate profits to retain long-term competitiveness, thus leading BDI to conclude that “we (Germany) cannot defend democratic values any better if we weaken ourselves economically.”

While in theory, this is a good idea, in practical terms it is a difficult case to make in the face of China’s suppression of the Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang and its crushing of Hong Kong’s democracy movement.

Earlier this year, Volkswagen, the world’s largest carmaker had come under scrutiny over operating a factory in Xinjiang, a region where incidences of large-scale human rights violations have been documented against the local Muslim minority.

The BDI assessment document notes, realistically that ‘transformation through trade’ has reached its limits” and goes on to say, “The expectation that global economic interdependence would automatically facilitate the spread and development of market economies and democratic structures has not come to pass.”

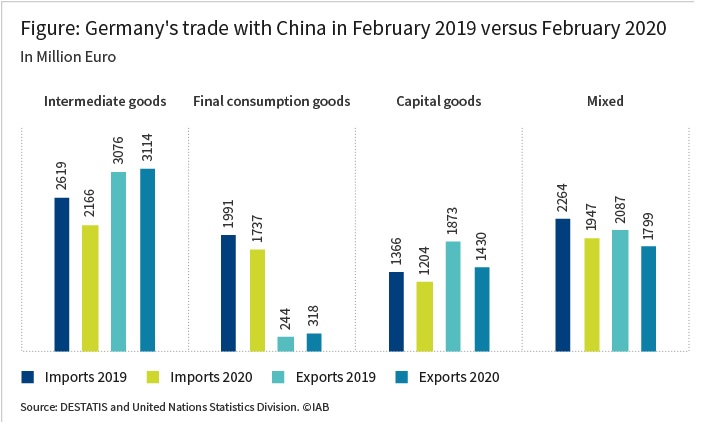

This indicates that German business must now decide their priorities and act accordingly. This of course, does not only concern China. One in four jobs in Germany depends on exports and despite persistent pressure from its partners, Germany has run one of the world’s largest trade surpluses for decades, much of it with countries like China and Russia.

While Germany has always traded with autocratic governments, it has never relied on one country to the extent it now relies on China.

China has driven much of the growth for demand in German machinery and autos in recent decades and has been Germany’s largest trading partner (combined exports and imports) for five years running.

Today many German industrialists realise that China, which has relied on their engineering acumen to modernize its economy, might not need them anymore.

Over time, China has become quite good at designing and building the specialized machinery, tools, and other equipment reducing its dependence on Germany.

The debate on policy towards China in Germany comes as the country’s political winds are shifting. Both the Greens and Liberal Free Democrats, the two parties who are expected to join the Social Democrats to form a new government, are likely to take a considerably harder line on China than the outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Among the BDI’s guidelines for Europe’s new foreign economic policy, for example, is a call for a stronger Euro relative to other currencies. It is argued that this “would provide Europe with more weight in the international payments system and global financial markets.”

Nils Schmid, the SPD’s foreign policy spokesman in the German Parliament, argues that Germany needs to push harder within the EU for a common stance on China, one that isn’t necessarily in opposition to the US, but that puts European interests first.

Germany’s incoming government needs to “strengthen the foundations for the ability to act — on the national as well as the European level,” he said. “Then there will be no need to declare a new Cold War with China.”

This is a significant new approach that will take time to deliver but has the inherent value to give practical shape to the hedging strategy that European business is already implementing.

References

1.https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/europes-magnesium-crunch-poses-another-carbon-conundrum-andy-home-2021-10-26/

- https://www.iab-forum.de/en/germanys-trade-with-china-at-the-beginning-of-the-global-covid-19-pandemic/

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments